In this blog post, our guest blogger Jim Laube (Founder & CEO of RestaurantOwner) will give you a short introduction to the concept of Prime Cost, one of the most important key performance indicators for your restaurant.

Table of Contents

It’s impossible to cost-control yourself to success in the restaurant business. However, it’s not uncommon for busy restaurants, even very high-volume ones, to show marginal returns and even losses due to poor controls, especially in the areas of food, beverage and labor costs.

While I don’t have any empirical evidence to back this up, 25-plus years of experience in the restaurant industry has led me to believe that uncontrolled food, beverage and labor costs are key contributing factors in the underperformance and eventual failure of just as many restaurants as undercapitalization, poor location and having an ill-conceived concept.

Not only is it very easy to lose money in these areas due to everything from waste, spoilage, theft and poor scheduling practices, but when there IS a problem, it’s usually a very expensive one, as the dollars add up very quickly.

Besides being a challenge to control, food, beverage and labor costs represent well over 50 percent of a restaurant’s total costs and nearly 90 percent of the costs that operators have any real control or influence over in the short term.

The Prime Cost Concept

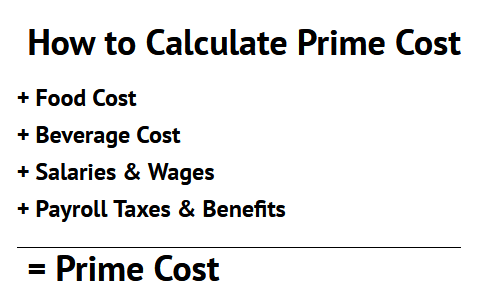

Due to the importance of containing food, beverage and labor costs, operators should approach them differently from any other costs on their profit-and-loss statement (P&L). This begins with looking at them combined as one cost category, which is referred to as a restaurant’s “prime cost”.

Prime cost is a restaurant’s total food, beverage and payroll costs for a certain period of time, say a month or week. In this calculation, payroll costs would include salaries and wages of working owners, managers and hourly employees plus the payroll taxes, benefits, workers’ compensation and other payroll-related expenses.

What Do You Look at First on Your P&L?

During my financial workshops I often ask operators what they look at first on their P&L. It’s common to hear, “the bottom line,” “food cost percent” or “sales”. However, whenever I look at a restaurant P&L, my eyes go first to prime cost. I usually have to calculate it manually, because rarely is prime cost a line item on the P&L, although it should be. (For more information, see “Make Your Profit & Loss Statement One of Your Most Powerful Tools.”) Prime cost is one of the best indicators of restaurant profitability and how well the business is managed on a day-in, day-out basis. Restaurants whose prime costs are out of control nearly always have issues with product consistency and food quality and for that matter, poor management practices. How a restaurant controls its prime cost is often a very telling indicator of how well the overall business enterprise is being managed.

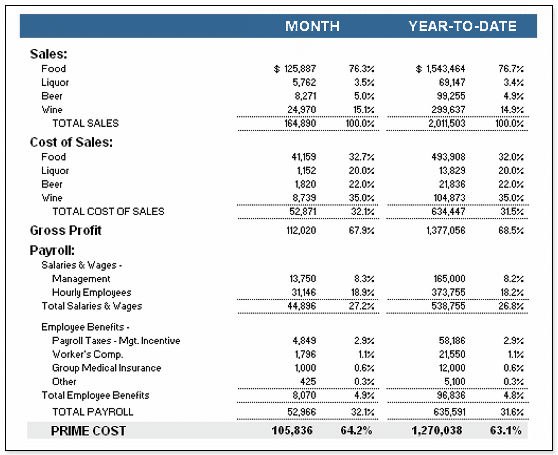

Since prime cost is such an important number, I recommend that operators have their accountant or bookkeeper modify their P&L to show prime cost as its own line item like this:

Presenting prime cost in this way brings it front and center whenever owners and managers look at their P&L.

What Should a Restaurant’s Prime Cost Run?

In table service restaurants, the generally accepted rule of thumb says that prime cost should run no more than 65 percent of total sales. Many of the larger, casual-theme chain operators are able to keep their prime cost 60 percent or less but for most table service independents, achieving a prime cost of 60 percent to 65 percent of sales still provides the opportunity to achieve a healthy net income provided a restaurant has a fairly normal cost- and-expense structure in the other areas of their P&L.

Profitability issues generally arise when prime cost exceeds 65 percent of sales and gets closer to 70 percent of sales. When this happens, it becomes increasingly difficult for nearly any table service restaurant to earn an adequate profit on the bottom line.

In some areas, state and local laws make it more challenging for restaurants to achieve a 65 percent prime cost because of the imposition of higher minimum wages and the disallowance of applying a tip credit to the wages of tipped employees. In states such as California, Oregon and Washington, operators can’t apply any portion of tips to the minimum wage calculation. Servers earn full minimum wage that can be well over $6 an hour plus their tips. However, the 65 percent or less prime cost threshold should still be considered appropriate, and operators should be especially vigilant about scheduling and other means of controlling their prime costs. Also, as much as is practical, menu prices should reflect the added cost of labor and, in essence, doing business in these states.

In quick-service restaurants, the goal is to keep prime cost at 60 percent of total sales or less. Some high-volume QSR (quick-service restaurant) operations have been known to achieve a prime cost of 50 percent or less and can generate as much as 20 percent to 25 percent net income as a percent of sales.

Why Not Just Focus On Food, Beverage and Labor Costs Individually?

Food, beverage and labor costs are important for any operator to know and track individually. No question about that. But it’s always important to look at these costs in proper context and that means in light of a restaurant’s prime cost as well.

Many operators have asked me how they’re doing with a certain food cost percentage of say 30 percent or 35 percent. It’s impossible to comment intelligently without considering several factors, including their menu offerings, portion sizes, price points, and sales mix. But most importantly, to give a meaningful assessment of a restaurant’s food or labor cost it’s necessary to also know the restaurant’s prime cost. By knowing a restaurant’s prime cost, one restaurant’s 35 percent food cost might appear excessive while another restaurant’s 40 percent food cost might appear quite good. Here’s an example. Some people might be surprised to learn that some of the most profitable restaurants in our industry have a food cost in excess of 40 percent. It’s true. I’m familiar with a seafood restaurant outside of a major metropolitan Midwest city that, according to reliable sources, consistently carries a food cost of 45 percent or higher, which is not all that uncommon in restaurants specializing in high-quality steak and/or seafood.

You might be wondering how any restaurant could make money, let alone be highly profitable, when its food cost is getting close to 50 percent of sales. Well, this particular restaurant does more than $20 million in annual sales in about 20,000 square feet. This means that its sales are more than $1,000 per square foot, which is probably one of the highest in the industry.

Now even though its food cost is high, at about 45 percent, what do you think its labor cost as a percentage of sales is when it generates a level of sales this high? I’m fairly certain it’s much lower than the industry average, which is around 30 percent to 35 percent. In fact, its payroll, including management, hourly staff and taxes and benefits is probably around 15 percent to 18 percent of sales, but let’s say it’s 20 percent to be conservative.

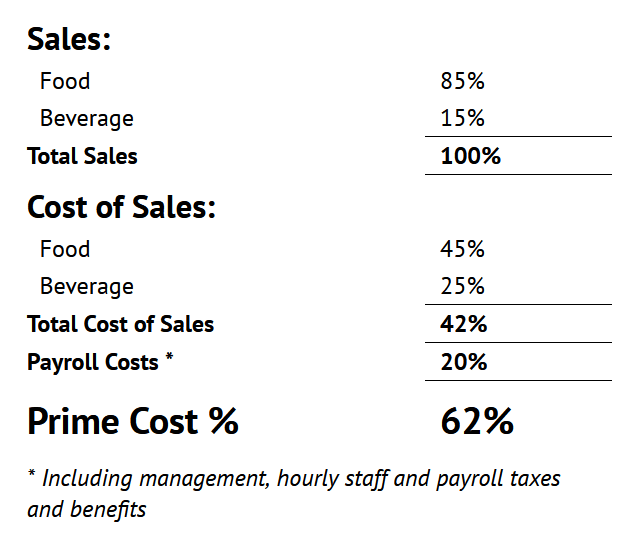

Let’s also assume that its sales mix is 85 percent food and 15 percent liquor, beer and wine. If its combined beverage cost is, say, 25 percent of beverage sales, here’s an estimate of its prime cost percentage:

If our assumptions about beverage and payroll costs are fairly accurate, you can see that the prime cost is well below the 65 percent threshold. This means that even with a very high food cost, this particular restaurant should be very profitable, assuming its remaining costs and expenses are in line with restaurant industry averages.

Some restaurants, like many ethnic concepts, have relatively low food costs, with some well under 30 percent of sales. You might think that these restaurants would be extremely profitable. They might be, but often these restaurants have lower check averages and are more labor-intensive, so their payroll costs are much higher as a percentage of sales than, say, a steak or seafood restaurant. Looking at cost of sales and payroll costs together as prime cost gives a much more meaningful and valid indication of a restaurant’s cost structure and potential for profit.

The starting point for determining the appropriateness of a restaurant’s food cost or labor cost should always be examining its prime cost.

Weekly is MUCH Better Than Monthly

Calculating prime cost once a month is just not sufficient. Nearly every chain operator and thousands of successful independents know this. Operators, be they chains or independents, who are really serious about maximizing their profitability, want to know their biggest most volatile costs, not just once a month, but at the end of every week. When prime cost is calculated weekly, operators and managers don’t have to wait until their monthly or four-week P&L is prepared to find out what happened in these important cost areas. If there’s a problem with food, beverage or labor, the weekly prime cost report puts them in a position to know about it and to react quickly.

In restaurants that only rely on the monthly P&L to track prime cost, what typically happens when there’s a big spike in, say, hourly payroll or liquor cost on the monthly P&L? What can the operator and managers do about it then? How long has the problem been going on? By the time they get their P&L, they’re probably half way through the following month and “it’s old news.” Also, what are the chances that someone will blame the spike on an “inventory” or “accounting” problem?

When prime cost is calculated at the end of every week the numbers become much more believable, because it’s easy to verify them, and when something is out of line, you’re in a much better position to react quickly, cut your losses and get the problem resolved.

Weekly prime cost reporting will change the culture in your kitchen because of the awareness and the sense of ongoing accountability it creates. If you’re only telling your chef or kitchen manager their food cost monthly, it’s really just an abstract, allusive number that happened in the past. Put them on notice by telling them that their food cost last week was three points higher than normal, and there’s a very good chance more attention will be paid to what’s happening in the kitchen and the problem will be gone by the time food cost is calculated next week.

Another benefit of weekly prime cost reporting is that it also makes managers more cognizant of the effect of their labor scheduling. When labor costs are reported each week, in the context of prime cost, the weekly employee schedule tends to get the attention and critical eye it deserves.

It’s very common for restaurants to see their prime cost go down by 2 percent to 5 percent of sales within the first few weeks of calculating these numbers weekly. Yes, it takes some time to calculate but by following the steps outlined below, the entire process to calculate prime cost should, in most restaurants, take just a few hours a week after a reasonable learning period.

A Quick and Easy Way to Know Your Prime Cost Each Week

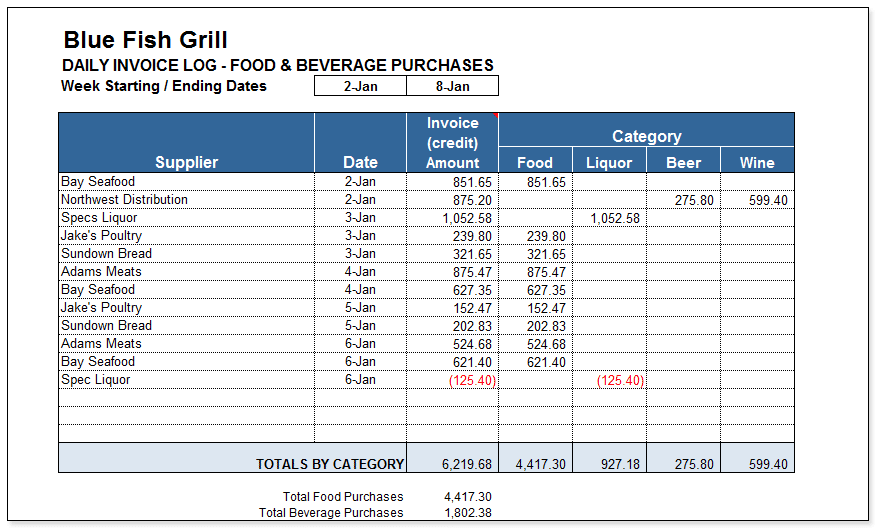

The first step in calculating the food cost part of prime cost is to keep a record of your daily food and beverages purchases on what some operators call an invoice log. Post or record your food and beverage invoices to the invoice log worksheet each day and indicate what amounts are chargeable to the appropriate food or beverage account categories.

Don’t forget to post credits for any product returns or invoice adjustments and be sure to record cash paid-out transactions for food and beverages purchases as well. At the end of the week the invoice log will give you the total of your restaurant’s food, liquor, beer and wine purchases. One suggestion: To save time in posting invoices, have your suppliers, particularly broad-line distributors, give you separate invoices for each major product type. Ask for a separate invoice containing just your food items, a separate invoice for cleaning supplies, paper goods and so on. This will make it much easier to log invoices into the proper accounts without having to manually break down and categorize the invoice line items manually. Also, most distributors can easily provide invoice subtotals of your food items by meat, seafood, poultry, grocery, etc., if you want this level of detail within your food cost account. (See “Daily Invoice Log – Food and Beverage Purchases” below).

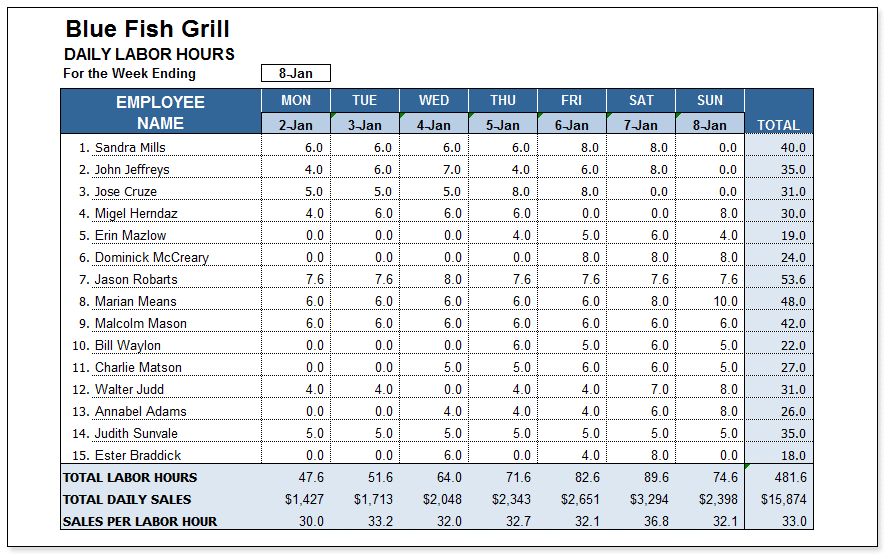

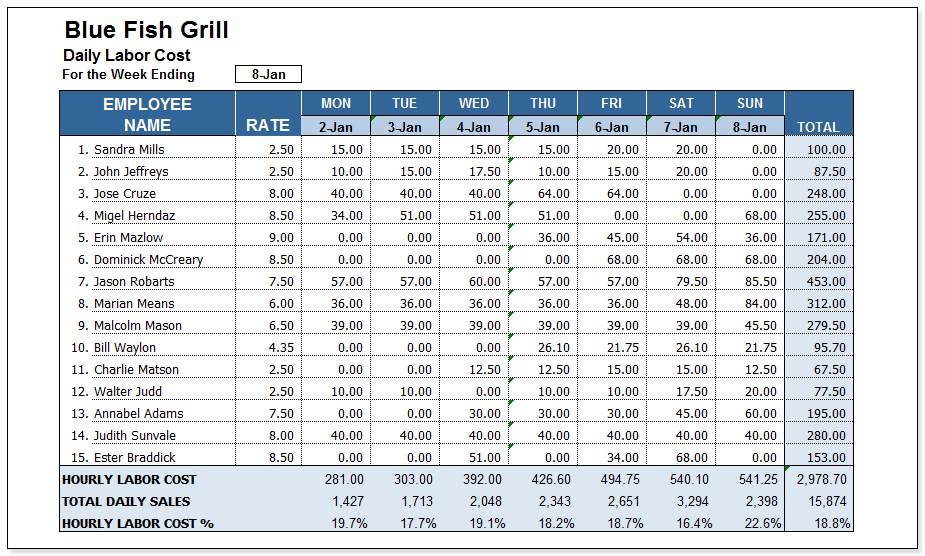

Using the “Daily Labor Hours” log (above), hourly labor cost should be calculated daily. If your POS or other timekeeping system calculates this for you, great; then you can just enter your hourly labor cost daily or at the end of the week. If your hourly labor cost isn’t available each day, you can easily calculate it with a simple worksheet like the one below. Just list your employees on the worksheet in the same order that their daily hours are printed on your timekeeping system. Post each employee’s total hours at the end of each day.

Link the “Daily Labor Hours” log and “Daily Labor Cost” (below). Each day you can enter the hours worked, and the worksheet calculates the hourly personnel labor cost.

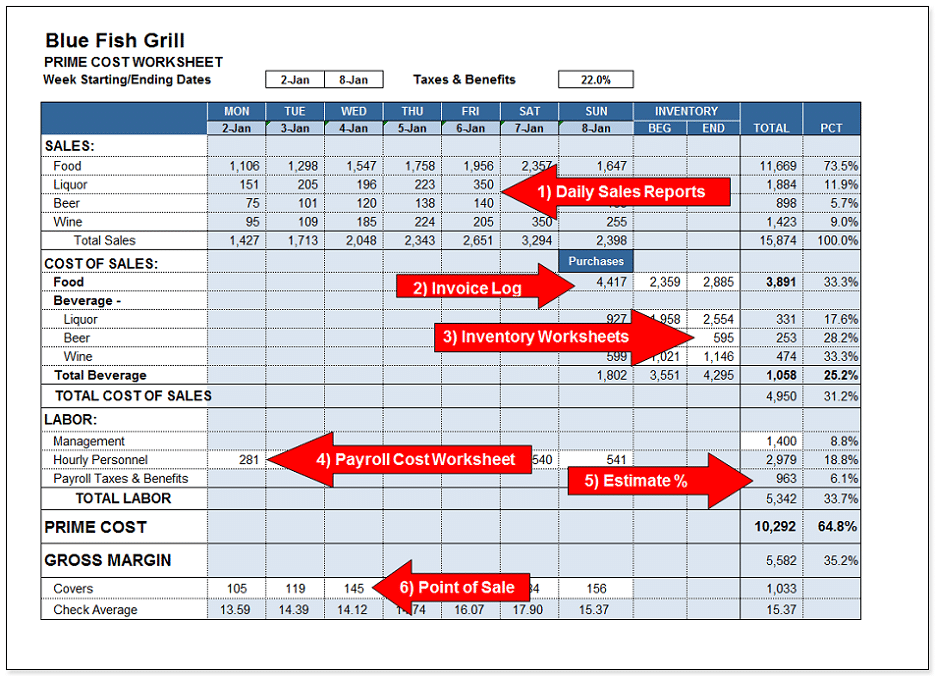

The “Prime Cost Worksheet” (above) allows you to enter the daily sales figures from your daily sales reports and your ending inventory from an extended inventory count sheet. Enter the daily sales figures from your daily sales reports and your ending inventory from an extended inventory count sheet. The beginning inventory is last week’s ending inventory. You can also add the number of covers served each day to get your daily and weekly check average. Here’s where the numbers on the worksheet come from:

Sales. Sales figures would come right off the restaurant’s daily sales reports.

Purchases. Food, liquor, beer and wine purchases would be automatically updated from the invoice log where daily purchases have been entered.

Inventory. If you want an accurate cost of sales number, plan on doing a physical inventory at the end of each week to calculate the value of your ending inventory. To save time, make sure the products on the inventory count sheet are in the same order as your products on the storage room shelves. Also, have two people count and one person record the quantities. Use a spreadsheet application to automate the calculations.

Also, consider ending your week on a Sunday. This is when your inventory is at the lowest levels of the week so there are fewer products to count. Many restaurants end their weeks on Sunday and have a team of people come in early every Monday morning to conduct the weekly physical inventory and prepare the weekly prime cost report. In some restaurants, the managers are responsible for preparing the entire prime cost worksheet including posting purchases on the invoice log and calculating hourly payroll. In other restaurants a bookkeeper or an administrative person assists the managers each week with the preparation of this report.

Labor. Enter the gross salaries of the management team for one week. The hourly personnel payroll should come from the hourly payroll worksheet above or from your time and attendance system if it calculates your hourly personnel gross payroll cost.

Payroll taxes and benefits. This is to account for the cost of employer payroll taxes, workers’ compensation, health insurance and other employee benefits. Payroll taxes and benefits usually run 20 percent to 23 percent of gross payroll cost in most restaurants. Ask your accountant if you have questions on this.

Covers. Enter the number of covers or total customers served each day if you also want to track the daily and weekly check average.

Once this information has been entered, operators now have the benefit of “knowing” the restaurant’s largest and most volatile costs of the previous week. Many operators that end their week on Sunday use this report as a regular topic of discussion at their weekly managers meeting Monday afternoon. Some compare the current prime costs numbers with last week’s results or create a kind of trend analysis worksheet on which they can see the results of several prime cost reports to track sales, cost of sales, labor costs and gross margin over several weeks.

Operators and managers have told me that once they got used to knowing their prime cost each week they didn’t know how they managed their restaurant without it.

If You’re Serious

Prime cost is one of the most important and revealing numbers on any restaurant’s P&L. It can give you a much better understanding of your cost structure, profit potential and how well your restaurant is being managed.

If you’re serious about controlling your costs and maximizing your profitability, take the time to calculate and track your prime cost each week. Weekly prime cost reporting will go a long way toward helping you better manage these costs and result in a measurable and material boost to your bottom line.

About the Author

Jim Laube, Founder & CEO of RestaurantOwner.com

Jim Laube founded RestaurantOwner.com in 1998. Jim has worked in the restaurant industry since high school, and has held positions as a server, bartender, manager, controller and CFO. He worked as an advisor and CPA to numerous independent restaurants for 15 years. In the mid-90s, Jim trained thousands of restaurant, foodservice, and financial professionals on restaurant accounting and controls in live seminars around the United States. Much of the materials created over those years became the foundation for RestaurantOwner.com.

Today, Jim is focused on developing more RestaurantOwner.com resources and training programs to help more independent restaurant success stories emerge.

About Zoined Restaurant Analytics

Zoined Restaurant Analytics helps you optimise your workforce and business, and is effortless to use and set up. Gain actionable insights related to sales, campaigns, working hours, and costs. Automate metric calculations such as calculating prime cost and other key metrics for your business.